Policy Options and Alternatives to Reduce Medicaid Costs

This is part three of a series I wrote on Medicaid spending reductions (proposed). Recent Republican budgets have targeted Medicaid for $800 plus billion in spending reductions. This final post in the series covers the likely choices available from a policy perspective, to achieve the savings target.

Parts one and two are available, here.

- Part I: https://rhislop3.com/medicaid-spending-reductions-what-to-know/

- Part II: https://rhislop3.com/medicaid-spending-reductions-part-ii/

Implementing Per-Capita Caps

Under current Medicaid financing, the federal government matches state expenditures without an upper limit, which has led to significant growth in program costs. A proposed alternative is the introduction of per-capita caps, which would limit federal spending per enrollee. This policy option aims to control costs by setting a fixed amount of federal funding per Medicaid beneficiary, adjusted for inflation or other factors.

While this approach provides predictability in federal spending, it could lead to funding shortfalls if healthcare costs rise faster than anticipated adjustments. States with higher-cost populations, such as those with larger elderly or disabled populations, may face disproportionate challenges. Unlike existing content that broadly discusses state-level implications, this section focuses specifically on how per-capita caps could compel states to make difficult trade-offs, such as reducing services or tightening eligibility criteria. For example, states might need to eliminate optional services like dental care or physical therapy (Grantmakers In Health).

Transitioning to Block Grants

Another frequently discussed policy option is transitioning Medicaid to a block grant model. Under this system, states would receive a fixed annual amount of federal funding, offering greater flexibility in program administration. However, this funding would not automatically adjust for changes in enrollment or unexpected costs, such as during economic downturns or public health emergencies (KFF).

This section differs from existing discussions on block grants by emphasizing the potential administrative challenges states may face. For instance, states would need to establish mechanisms to allocate limited funds, potentially leading to disparities in access to care. Moreover, block grants could incentivize states to reduce enrollment or benefits to stay within budget constraints, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations such as children and individuals with disabilities.

Adjusting Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP)

The Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) determines the federal share of Medicaid costs, with higher rates provided to states with lower per-capita incomes. Adjusting FMAP rates is another proposed strategy to reduce federal Medicaid spending. For example, lowering the FMAP for Medicaid expansion populations or optional services could shift more financial responsibility to states (CRFB).

This section builds on existing content by exploring how FMAP adjustments could create inequities among states. Wealthier states with more robust tax bases may be better equipped to absorb the additional costs, while poorer states could struggle to maintain current coverage levels. Additionally, FMAP reductions might discourage states from expanding Medicaid or maintaining optional benefits, further limiting access to care for low-income populations.

Limiting Medicaid Eligibility

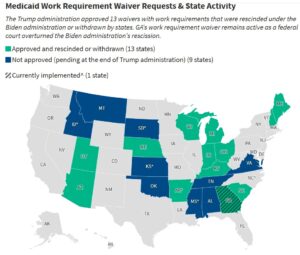

Restricting Medicaid eligibility criteria is another cost-saving measure under consideration. This could involve tightening income thresholds, imposing work requirements, or excluding certain populations, such as undocumented immigrants. While previous sections have touched on eligibility reductions, this section delves into the specific mechanisms and their potential impacts (Healthcare Business Today).

For example, work requirements could lead to disenrollment among individuals unable to meet the criteria due to caregiving responsibilities or unstable employment. Similarly, excluding undocumented immigrants could reduce Medicaid enrollment but may increase uncompensated care costs for hospitals. These measures could also exacerbate health disparities, as vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected by stricter eligibility rules.

Reducing Provider Payment Rates

Lowering reimbursement rates for Medicaid providers is another policy option aimed at reducing program costs. While Medicaid already reimburses providers at lower rates than Medicare or private insurance, further reductions could discourage provider participation, limiting access to care for beneficiaries.

For instance, rural areas, which already face provider shortages, may experience even greater challenges in maintaining adequate access to care. Additionally, reduced payment rates could lead to longer wait times and lower-quality care for Medicaid enrollees. Providers may also shift costs to privately insured patients, increasing overall healthcare expenditures.

Reforming Medicaid Expansion

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) allowed states to expand Medicaid eligibility to low-income adults without children, with the federal government covering 90% of the costs. Some proposals suggest rolling back this expansion or reducing the federal match rate for expansion populations as a cost-saving measure (KFF).

States that have expanded Medicaid may face significant budget shortfalls if federal funding is reduced, potentially leading to coverage losses for millions of low-income adults. Additionally, hospitals and other providers that rely on Medicaid expansion funds to offset uncompensated care costs could face financial strain, particularly in states with high uninsured rates.

Introducing Value-Based Payment Models

Shifting Medicaid payments from fee-for-service to value-based models is another proposed strategy to control costs. These models tie provider payments to patient outcomes rather than the volume of services delivered, incentivizing efficiency and quality care (Healthcare Business Today).

Preliminary successes in controlling costs and institutional utilization, demonstrated by I-SNP and C-SNP plans provide a possible pathway for other value-based payment models.

Som providers however, serving high-risk populations may struggle to achieve the required outcomes, leading to financial penalties. Additionally, the upfront costs of transitioning to value-based care, such as investing in data analytics and care coordination, could be prohibitive for smaller providers. Despite these challenges, value-based models have the potential to generate long-term savings by reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and improving chronic disease management.

Modifying Benefits and Coverage

Reducing or eliminating optional Medicaid benefits, such as dental, vision, and mental health services, is another cost-containment strategy. While mandatory benefits like hospital and physician services must be covered, states have discretion over optional services (Grantmakers In Health).

For example, cutting dental services could lead to untreated oral health issues, which are often linked to chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease. Similarly, reducing mental health services could exacerbate ongoing mental health crises, increasing costs for emergency care and law enforcement. These cuts may offer short-term savings but could result in higher long-term costs for states and the federal government.

Addressing Prescription Drug Costs

Prescription drugs account for a growing share of Medicaid spending, making them a target for cost-containment initiatives. States have implemented various strategies, such as negotiating supplemental rebates, using preferred drug lists, and adopting value-based purchasing agreements (KFF).

One option is allowing Medicaid to directly negotiate drug prices or implementing price caps for high-cost medications. While there is some possibility such a move could generate significant savings, similar approaches under Medicare haven’t see much savings and ultimately, cost shifts in the form of higher premiums on Medicare Advantage plans. These measures may face resistance from the pharmaceutical industry and require legislative action. Additionally, policymakers must balance cost containment with ensuring access to innovative therapies for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Enhancing Program Integrity

Improving program integrity to reduce fraud, waste, and abuse is another strategy to lower Medicaid costs. This includes measures such as enhancing eligibility verification, auditing provider claims, and implementing data analytics to detect improper payments (CRFB).

Implementing stricter eligibility verification processes may inadvertently disenroll eligible beneficiaries, increasing, albeit in small measure, uninsured rates. Additionally, auditing and data analytics require significant administrative resources, which may strain state Medicaid agencies. Despite these challenges, improving program integrity could yield substantial savings while preserving access to care for eligible individuals. It is estimated that as much as $50 billion is incurred by Medicaid annually, on improper payments 5 Key Facts about Medicaid Program Integrity | KFF .

Conclusion

The proposed Medicaid spending cuts, outlined in the recent House budget resolution, represent one of the most significant challenges to the program in its history, with $880 billion in reductions over the next decade. These cuts, aimed at addressing the federal deficit, could profoundly impact Medicaid’s ability to provide healthcare coverage to millions of Americans. Key proposals include eliminating the 90% federal match rate for Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), transitioning to block grants or per-capita caps, and reducing provider reimbursement rates.

The implications of these cuts are far-reaching. States would face difficult decisions, such as raising taxes, reducing eligibility or benefits, or adopting cost-sharing measures, all of which could disproportionately harm some low-income and underserved communities. Additionally, healthcare providers, particularly safety-net hospitals and long-term care facilities, may experience financial strain, potentially reducing their ability to serve Medicaid patients. Broader consequences could include increased uninsured rates and added financial strain on the U.S. healthcare system, as more individuals turn to emergency services for care.

Policymakers must carefully weigh the trade-offs of these proposed cuts. While cost-containment strategies such as value-based payment models and enhanced program integrity offer potential savings, they require thoughtful implementation to avoid unintended consequences. Public opposition to Medicaid reductions, coupled with political resistance in the Senate, suggests that the future of these proposals remains uncertain.

In the end, the overall challenge remains…reducing federal budget deficits and in turn, ultimately shrinking the impact of our current $36 trillion debt (that is rapidly rising). Entitlement and social benefit programs like Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security account for the largest share of government spending. Unless some resolution can be made to have these programs become more fiscally stable, less bureaucratic, and more socially accountable, their overall burden will ultimately accelerate an economic collapse for the U.S. – save massive tax increases and even then, the ultimate outcome is only deferred.