Late last week, I posted the first part of a three-post, comprehensive review of Medicare hospice and home health fraud. Medicare home health and hospice billing fraud has emerged as a significant issue within the U.S. healthcare system, costing taxpayers billions of dollars annually and jeopardizing the integrity of federal health programs. This is part two. Part one is available here https://rhislop3.com/medicare-hospice-and-home-health-fraud-part-1/

Patterns of Fraudulent Activity in Home Health Billing

Fraudulent practices in Medicare home health billing often involve intentional misrepresentation of services to maximize reimbursements. These schemes exploit the vulnerabilities in Medicare’s reimbursement processes, leading to significant financial losses and compromised patient care. Some of the most notable patterns include:

Billing for Services Not Provided

A common fraudulent tactic is submitting claims for services that were never rendered. For instance, home health agencies may bill Medicare for visits or treatments that did not occur, inflating their revenue while providing no benefit to patients.

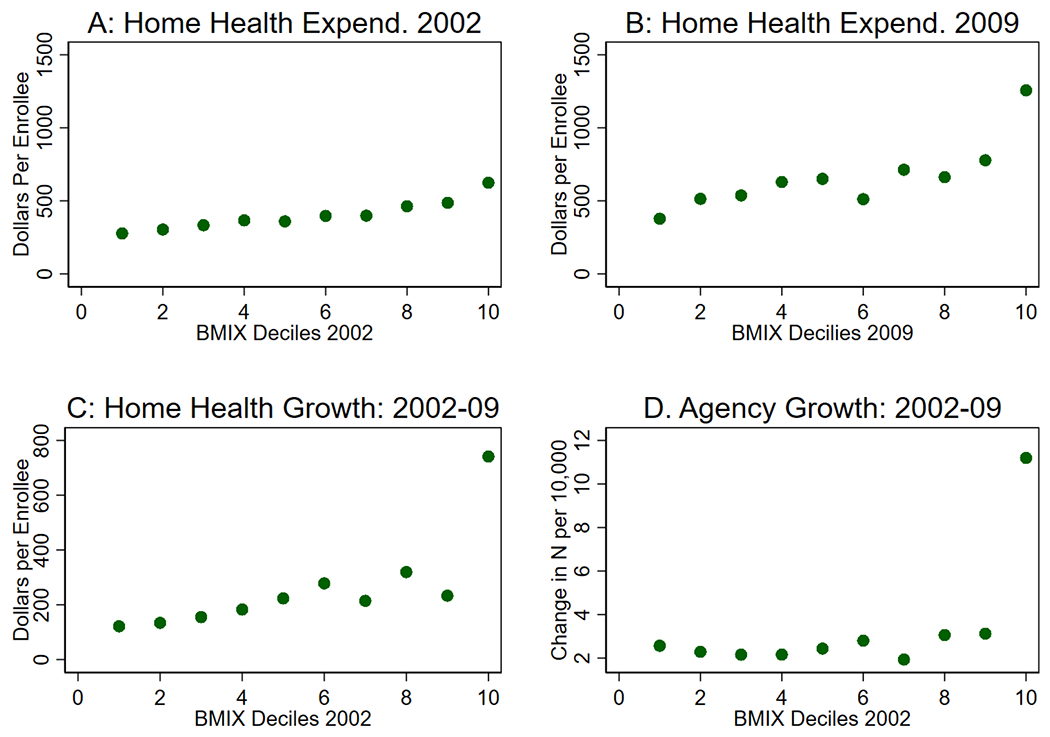

According to a study by Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, agencies with unusually high expenditures in specific hospital referral regions (HRRs) were more likely to engage in such fraudulent practices. The study link is here: The Diffusion of Health Care Fraud: A Bipartite Network Analysis – PMC

Falsified Patient Eligibility

Fraudulent providers often falsify patient records to make them appear eligible for Medicare-covered home health services. This includes altering documentation to show patients as homebound or requiring skilled nursing care when they do not meet these criteria. Such actions undermine the integrity of the Medicare system and divert resources from patients who genuinely need care.

Kickback Schemes

Kickbacks are another prevalent issue in home health fraud. Agencies may pay illegal incentives to physicians or clinics to refer patients, even when those patients do not require home health services. A case reported by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) highlighted how clinics received kickbacks for fraudulent certifications, resulting in unnecessary Medicare expenditures.

Upcoding of Services

Upcoding refers to billing for a higher level of service than was actually provided. For example, a provider may claim reimbursement for complex medical procedures when only basic care was delivered. This fraudulent practice inflates costs and misuses Medicare funds.

Duplicate Billing Across Agencies

The Dartmouth study also identified instances where patients were shared across multiple agencies, leading to duplicate billing for the same services. This practice not only defrauds Medicare but also creates confusion in patient care coordination.

Geographic Hotspots for Fraudulent Practices

Certain regions in the United States have been identified as hotspots for Medicare fraud in home health and hospice care. These areas often exhibit disproportionate billing patterns compared to national averages.

High Expenditure Regions

Regions such as McAllen, Texas, and Miami, Florida, have consistently shown unusually high Medicare expenditures for home health services. Between 2002 and 2009, the average billing per Medicare enrollee in these areas increased significantly—by $2,127 in McAllen and $2,422 in Miami—compared to a national average increase of $289 (Home Health Care News).

Targeted DOJ Investigations

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has focused its enforcement efforts on these high-expenditure regions, uncovering systemic fraud and abuse. Investigations have revealed that certain agencies in these areas disproportionately engage in practices such as billing for unnecessary services or falsifying patient eligibility.

Urban vs. Rural Disparities

Urban areas tend to report higher instances of fraud due to the concentration of providers and patients, making it easier for fraudulent actors to exploit the system. However, rural areas are not immune, as limited oversight in these regions can also create opportunities for abuse.

Common Fraudulent Practices in Hospice Billing

Hospice care fraud poses unique challenges, as it often involves the misrepresentation of patient eligibility and the level of care provided. Key fraudulent practices include:

False Certification of Terminal Illness

Hospice fraud frequently involves certifying patients as terminally ill (with a life expectancy of six months or less) when they do not meet this criterion. According to Senior Medicare Patrol, some providers falsely certify patients to enroll them in hospice care, thereby billing Medicare for services the patients do not need.

Enrollment Without Consent

Fraudulent hospices have been known to enroll patients without their or their families’ knowledge or consent. This unethical practice not only defrauds Medicare but also deprives patients of appropriate care options.

Billing for Higher Levels of Care

Similar to upcoding in home health, hospice providers may bill for more intensive levels of care than were actually provided. For example, a hospice may claim reimbursement for continuous care when only routine care was delivered (AAPC Knowledge Center).

Offering Incentives for Referrals

Kickbacks and other incentives to physicians or patients for hospice referrals are another common issue. Such practices violate the Anti-Kickback Statute and undermine the ethical provision of care.

Inadequate or Incomplete Services

Fraudulent hospices may fail to provide the full range of services outlined in a patient’s care plan, resulting in substandard care while still billing Medicare for the full amount (Medicare Interactive).

Financial Impact of Medicare Fraud in Home Health and Hospice

The financial repercussions of Medicare fraud in home health and hospice care are significant, with billions of dollars lost annually to fraudulent activities.

Overall Financial Losses

The HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) reported recovering $3.44 billion in misspent Medicare and Medicaid funds during Fiscal Year 2023. While not all of this amount is tied to home health and hospice fraud, these sectors represent a substantial portion of the problem.

Hospice-Specific Losses

In 2023, suspected hospice fraud amounted to an estimated $198.1 million, with $143.81 million in alleged fraudulent activity reported in 2024 alone (Hospice News).

Impact on Taxpayers

Fraud in these sectors not only drains Medicare funds but also imposes a financial burden on taxpayers. The Fraud Fighters Network estimates that fraudulent home health practices cost American taxpayers billions of dollars annually.

Cost of Enforcement

Combating fraud requires significant investment in audits, investigations, and legal actions. While these efforts recover substantial funds, they also highlight the systemic vulnerabilities that allow fraud to persist.

Regulatory and Enforcement Efforts

To address the pervasive issue of Medicare fraud in home health and hospice care, regulatory agencies have implemented several measures:

Enhanced Oversight by CMS

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has intensified its program integrity strategies, focusing on identifying fraudulent actors and minimizing their impact on beneficiaries (Hospice News).

DOJ and OIG Investigations

The DOJ and OIG have ramped up enforcement actions, targeting fraudulent providers through audits, investigations, and prosecutions. These efforts have led to significant recoveries and the dismantling of fraudulent schemes.

Policy Changes

The OIG’s recommendation to establish a hospital transfer payment policy for early discharges to hospice care has saved Medicare $545 million since its implementation in 2019 (AAPC Knowledge Center).

Public Awareness Campaigns

Organizations like Senior Medicare Patrol and Medicare Interactive provide resources to educate beneficiaries and their families on identifying and reporting fraud.

Technology and Data Analytics

Advanced data analytics are being used to detect suspicious billing patterns and identify potential fraud. For example, overuse of specific HCPCS codes has triggered investigations by Special Investigative Units (SIUs) (Cotiviti).

Part three will drop toward the end of this week!

1 thought on “Medicare Hospice and Home Health Fraud, Part 2”