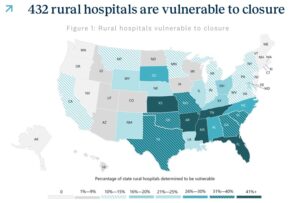

According to a Feb. 11 report by Chartis, 432 rural hospitals are at risk of closure. Chartis analyzed 15 indicators and identified 10 significant predictors, including Medicaid expansion status, average length of stay, occupancy, changes in net patient revenue, and years of negative operating margin. The full report is available here: CCRH WP – 2025 Rural health state of the state_021125

Out of 48 states with rural hospitals, 38 have at least one at risk. States most affected are:

- Texas: 47

- Kansas: 46

- Mississippi: 28

- Oklahoma: 23

- Georgia: 22

NOTABLE POINTS

- In the 10 states yet to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), 53% of rural hospitals are operating in the red.

- 293 rural hospitals stopped offering OB services between 2011 and 2023, while 424 ceased chemotherapy services between 2014 and 2023.

- Policies such as sequestration and bad debt reimbursement will cost rural hospitals more than $650 million this year.

- Social drivers of health indicators show rural communities have lower median household income (-36 percentile points) and higher rates of child poverty (+16 percentile points) when compared to their urban peers.

- Rural Americans carry a larger share of the chronic disease burden with higher rates of adult obesity (+30 percentile points) and have higher rates of premature death (+20 percentile points) than their urban counterparts.

- Nearly 25% of all veterans reside in rural communities. Access to care challenges mean that this segment is particularly vulnerable.

NO MARGIN, NO MISSION

Nearly half of all rural hospitals are operating at a loss. Hospitals without positive margins struggle to fulfill their mission of providing care for vulnerable communities. Rural patients in need often rely on hospitals that are reducing services or facing closure. Currently, the national median operating margin for rural hospitals is 1.0%, but in 16 states, it is negative. In Connecticut, all rural hospitals are operating at a loss. In Kansas, 87% of rural hospitals are in the red, followed by Washington (76%), Oklahoma (70%), and Wyoming (70%). Conversely, less than 20% of rural hospitals in Alaska (15%) and Wisconsin (19%) are operating at a loss.

In rural areas, 39% of Medicare-eligible individuals are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans. This shift affects rural hospitals used to Traditional Medicare processes and reimbursement.

Medicare Advantage often uses fee-for-service reimbursement as a percentage of Medicare rates, rather than cost-based reimbursement. Consequently, rural hospitals may receive lower payments for these patients. Additionally, like private health plans, Medicare Advantage requires prior authorizations, which can lead to denials and more administrative work.

SHRINKING BED CAPACITY

No metric has better illustrated the challenges faced by rural hospitals since 2010 than facility closures. Over the past 15 years, 182 rural hospitals have either closed or transitioned to an operating model that does not offer inpatient care, such as long-term care or becoming a Rural Emergency Hospital (REH). This figure represents approximately 10% of the nation’s rural hospitals. For impacted communities, the loss of a rural hospital can lead to economic difficulties and deteriorating community health status.

Seven states have experienced double-digit losses in inpatient care through closures or conversions. Texas and Tennessee have been most affected, with 26 and 16 losses respectively. Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, and Oklahoma are tied for third place, each losing inpatient care in 11 communities. The highest rates of inpatient care loss are seen predominantly in the South, spanning from the Carolinas to Texas, and extending into the Midwest. Conversely, states along the Rockies and the Pacific Northwest have, so far, largely avoided significant inpatient care reductions.

Chartis’ analysis (the report available in paragraph 1) of inpatient care loss includes facilities opting for the REH designation, as this conversion necessitates the cessation of inpatient care services. Nationally, 32 rural hospitals have converted to REH since January 2023. Last year’s total conversions (17) were slightly lower than the 19 conversions recorded in 2023. Our examination of REH prospects and the propensity of rural hospitals to pursue conversion indicates that approximately 400 facilities are “most likely” to consider REH, with 77 identified as prime candidates for this new designation. More on Rural Emergency Hospitals is available at a post I wrote last January https://rhislop3.com/rural-hospital-program-extra-cash-for-emergency-and-outpatient-services-stuck-in-neutral/

BOTTOM LINE

The fundamental reason rural hospitals face dire financial straits is low payments from private insurers, predominantly and growing, Medicare Advantage. Though facilities may lose money on reimbursements from public payers such as Medicaid, about half of the services at rural hospitals are delivered to patients with private insurance — and the reimbursement from these insurers does not cover the higher costs of care.

Hospitals in rural communities have a smaller population to serve, meaning less revenue from patient care. But expenses are often fixed. For example, an emergency department still needs to be staffed 24/7, even if fewer people need services. More than 700 rural hospitals at risk of closing: report | Healthcare Dive